Kootenai Brown Poplar Grove Cabin Site

This site was rediscovered in 2016 by Edwin Knox, retired Waterton Lakes National Park Warden/Cultural Resource Management [1]. Initially, the search was for the location of John George “Kootenai” Brown’s cabin that now resides in the Kootenai Brown Pioneer Village. Upon the rediscovery of this location and exploration of the area seven culturally modified trees (CMTs) were identified. The poplar trees contain carvings of dates and initials from 1882 to 1929. The increase in wildfires and that poplar trees are prone to rot [2] poses a risk to these 140 year old carvings. One tree has already fallen and it was imperative that these trees be digitally preserved for prosperity.

Region:

Southwest Alberta

Field Documentation:

May 27, 2022

Field Documentation Type:

Terrestrial LiDAR

Culture:

Euro-Canadian, Metis

Historic Period:

1882CE

Latitude:

49.260728

Longitude:

-113.202074

Datum Type:

Threat Level

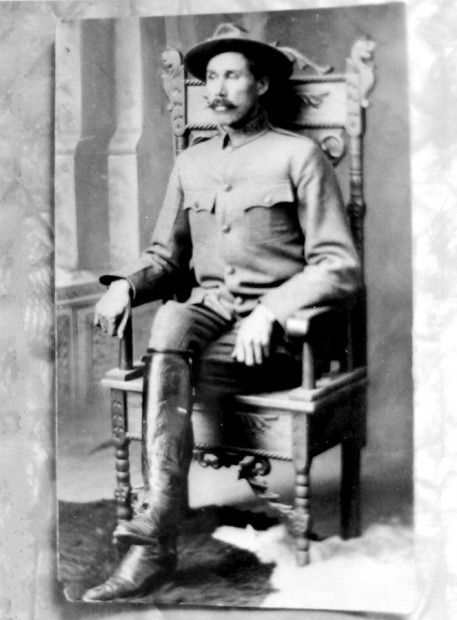

John George “Kootenai” Brown

John George Brown was born in Ireland Ennistymon, County Clare, on the 10th October 1839, to John George Brown and Ellen Finucane [3]. Orphaned at a young age, he was raised by his grandparents who obtained him commission in the British Army in 1857 where he served briefly in India [3]. By 1861 he left the army and set out for the Cariboo gold-field in British Columbia [3]. Brown was unsuccessful in the pursuit of gold in Vancouver and Wild Horse Creek and in 1865 was briefly employed as constable in Wild Horse Creek [3]. Trying his hand again at prospecting Brown set out for Fort Edmonton in the July of 1865 [3]. Having encountered a Blackfoot war party and disagreements between himself and his traveling companions the company split and he never arrived in Fort Edmonton [3]. Instead he made his way to Duck Lake, SK, where he wintered with the Metis before making his way to Upper Fort Garry in the spring of 1866 [3]. By 1867 he became a mail carrier for a private company that serviced the United States Army in Dakota and Montana, but the enterprise failed by 1868 [3]. The army continued Browns services and hired him for the next six years as a carrier, contractor, guide and interpreter [3]. In 1868 Brown married Olive Lyonnais and after leaving the army’s employment in 1874 joined the Métis community which Olive belonged [3]. Brown’s love affair with the Kootenay (now Waterton) Lakes started when he first passed through the area on his trip that set out for Fort Edmonton and vowed to live in the area [3].

In 1877 he eventually moved with his wife, Olive, and their daughter and son where he supported his family by trapping and fishing and periodical jobs as a packer and guide for the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) [3, 4]. Somewhere between 1883 and 1885 Olive passed away [3]. A few years later Cheepaythaquakasoon (“blue flash of lightening” aka Isabella [1]), a Cree woman, came to live with Brown as his country wife [3]. Between 1885 and 1888 Brown was a scout and guide for the Rocky Mountain Rangers and the NWMP and by 1889 was employed as a packer for the Canadian Pacific Railway [3]. With the expansion of the railway into western Canada more visitors were coming to the Kootenay Lakes which provided employment as a guide for Brown, but also raised concerns about the impacts on the local flora and fauna of the area [3]. By 1895 Ottawa set aside a township and half for the Kootenay Lakes Forest Reserve where Brown became the fishery officer in 1901 and held the post until 1912 with additional responsibilities added as forest ranger in 1910 [3, 1]. During this period Brown persistently stressed the need for great conservation measures and by 1914 the reserve was greatly expanded based on Brown’s recommendations. The reserve was renamed Waterton Lakes National Park where Brown was park ranger until his death, 18th July 1916 [3].

Rediscovery of “Kootenai” Brown’s Cabin

There were already four known cabin locations occupied by Kootenai Brown, three with in a stone’s throw of the Waterton River:

- Kanoose-Brown Trading post on the east side of Lower Waterton Lake near Maskinonge;

- in the meadow north of the present park kiosks; and near todays present day-use-area Hay Barn)

- and one in the Parks Canada lower compound [1].

A fifth cabin known to have been occupied by Kootenai Brown was removed from its original location in 1970 when concerns were raised about its condition and placed in the Kootenai Brown Pioneer Village [1]. The exact location of this cabin was lost and to mark the centennial of the passing of Kootenai Brown in 2016, Edwin Knox former Parks Canada Warden and Cultural Heritage Manager started the search for the location of this fifth cabin [1]. Reading newspaper articles of the cabins move and talking to locals, Edwin had a rough area of where to start his search [1]. He headed to the Parks archives to look at historical aerial photographs where he found a cabin clearly visible in 1939 [1]. To confirm the location Edwin made a site visit with newspaper photographs of the move and matched the mountains in the background [1], which placed him in a small depression where the foundations of the cabin would have once been [5]. The cabin stood in this location from 1905 and was abandoned by 1911 when Kootenai and Cheepaythaquakasoon moved to their final home in the parks lower compound [1]. In rediscovering this location, Edwin also identified an old trail that crossed the cabin location, which does show on early maps, and seven culturally modified trees (CMTs). Each tree has at least one set of initials and a date.

- A heart with a stylized “JC” & “29”

- “ZEKE 88”

- “TP 06”

- “DRP”, “P”, & “94” and “W?” “83”

- “MP 82” and “NP 83”

- “PP” & “KL”

- “NWP 83”

The first tree had a unique and identifiable mark of Joseph Clarence Cosley, who was renowned for marking trees this way [1, 6]. With such a recent discovery more research needs to be done into the other remaining marks, but it has been hypothesized that they could relate to the North-West Mounted Police (tree 3 & 7) as they would have been in the area of from 1874 when they arrived in Fort Macleod and we know that the “police” often visited Kootenai while he was living in the area from his letters and diaries [1].

Culturally Modified Trees (CMTs)

CMTs are trees that have been cut into and scared by humans [6]. The modification of trees can be for a variety of reasons from food to clothing [6] and is largely associated with first nation groups in Western Canada [7]. In Glacier National Park (GNP) in the United States, which adjoins Waterton Lakes National Parks boarder, also recognises the marks that were made after contact with European settlers, in particular the early Park Rangers who were marking trails or just leaving their mark [6]. One of those rangers in GNP was Joe Cosley, who traveled the Belly River trail [4]. The Belly River flows north from GNP into Waterton Lakes National Park and then turns northeast and flows into Oldman River in Alberta [8].

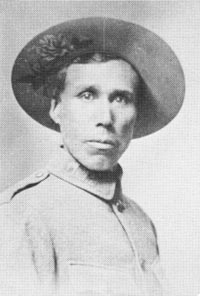

Joseph Clarence Cosley

Joseph (Joe) Clarence Cosley was born in 24th May 1870 on the Seven Nations Reserve in Ontario to a French-Canadian father and Métis mother [9, 10]. Not much is known of Cosley’s early life, other than he attended the Shingwauk Residential School between the ages of 8-11, with his remaining education undocumented [9]. By 1887 Cosley moved west to Montana to punch cows (herd cows) [9, 10]. In 1890 he assisted Lt. George Ahern in building the Ahern Pass, which became a favorite escape route for Cosley in later years, and by 1891 had Cosley Lake and ridge named after himself [10, 11]. This was the beginning of a 40 year venture in the region, especially along the Belly River trail and has since become known as Cosley Country [10]. Cosley met Kootenai Brown in October 1894 [12], who is thought to have influenced some of Cosley’s lifestyle choices [10]. Cosley soon set himself up as a fur trapper and maintained over 200 miles (roughly 320 km) of trap lines that crossed from what would become Waterton Lakes National Park and Glacier National Park [9]. By 1900 Colesy had become a U.S. National Forest ranger and when the Glacier National Park was formed he became a GNP ranger in 1910 and was permanently assigned to the Belly River District [10]. Up until his dismissal in June 1914, Cosley continued to trap in the region even though it was against the law and it was this behavior that finally lost him his position as ranger [10]. Soon after in August of 1914 he enlisted in World War 1 and joined the Cardston Troop in “C’ Squadron 13, in the Canadian Mounted Rifles [10]. When the war was over Cosley returned to the area in 1919 and became a guide but also continued with his trapping and poaching in both parks [10]. It wasn’t until 6th May 1929 that his illegal actives got him into trouble and he was arrested by the then Belly River District ranger Joseph F. Heimes. This arrest resulted in what was thought to be the “trial of the century”, but on the 10th May 1929 Cosley’s friends paid his bail and collected his cache of furs and traps. Cosley made his way over the Ahern Pass to Canada and proceeded to sell the furs [10]. Cosley spent his remaining days trapping and prospecting while heading further north in Alberta and Saskatchewan [10]. Cosley passed away from scurvy in 1943 in a trappers cabin in northern Saskatchewan, but was not discovered until 1944 [10].

While Cosley was best known for his adventures as a trapper and poacher he was also renowned as a storyteller, writer, and artist with much of his works published in his day [1, 10, 12]. In addition Cosley’s mark has been left across the Belly River region in the form of carvings on trees and are thought to number into the 100s, but due to there often remote locations remain hidden [10]. The earliest discovered was in 1887 in Kishinena (British Columbia), Montana [10] with this latest discovery possibly being one of his later tree carvings from 1929. The carvings usually contain his initials or full name and a date, often a heart and sometimes the initials of a loved one. For example, Helen P. Clarke was a known love interest of Cosely’s and several trees with his initials and H.C. have been found in the region [10].

Biological Cultural Heritage

Biocultural heritage is still a term that is developing [13], but broadly encompass the natural–cultural components of human–environment interactions including knowledge, practices and innovation [14]. Further development of the term has defined four interactive elements that are interlinked at temporal and spatial scales and only understood through integrated landscape analysis [14]. Ecosystem memories are the long lasting effects of human actives on both the biological and landscape structures, such as fire management or agriculture [13]. Landscape memories are the human practices and ways of organizing landscapes [14], such as the trails used by the First Nations groups of the region and the early European settlers or the carving of trees or building a cabin. Place memories are the intangible human knowledge of landscapes, such as place names, that are passed from one generation to the next and change over time [14]. Stewardship and change is a reservoir of knowledge and experience for landscape management [14], such as Parks Canada or the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Notes

This site is located on Treaty 7 Territory of Southern Alberta, which is the traditional and ancestral territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy: Kainai, Piikani and Siksika as well as the Tsuu T’ina Nation and Stoney Nakoda First Nation. This territory is home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3 within the historical Northwest Métis Homeland. We acknowledge the many First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have lived in and cared for these lands for generations. We are grateful for the traditional Knowledge Keepers and Elders who are still with us today and those who have gone before us. We make this acknowledgement as an act of reconciliation and gratitude to those whose territory we reside on or are visiting.

[1] Knox, Edwin, 2021, Historical Background of the Kootenai Brown “Poplar Grove” Cabin.

[2] Christensen, Julie, 2017, Strength of Poplar Trees, electronic document, accessed 02-06-2022.

[3] William Rodney, 2003, “BROWN, JOHN GEORGE, Kootenai Brown,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed June 3, 2022, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_john_george_14E.html.

[4] William, Rodney, 1973, Kootenai Brown: Life and Times. Gray’s Publishing Ltd, Sidney, British Columbia, Canada.

[5] Personal Communication, 2022, Edwin Knox.

[6] National Parks Services, 2017, Culturally Modified Trees Study, electronic document, accessed 02-06-2022.

[7] Archaeology Branch, B.C. Ministry of Small Business, Tourism and Culture, 2001, Culturally Modified Trees of British Columbia A Handbook for the Identification and Recording of Culturally Modified Trees, electronic document, accessed 02-06-2022.

[8] Crown of the Continent: Belly River, Waterton National Park , Alberta. Electronic Document, accessed 02-06-2022.

[9] Park Cabin Company, 2019, The Inimitable Life and Death of Joe Cosley, electronic document, accessed 03-06-2022.

[10] McClung, Brain, 2009, Belly River’s Famous Joe Cosley (Third Edition), Life Preservers Publishing LLC.

[11] Ahern, Dennis, 2010, Lieutenant George Patrick Ahern and Glacier National Park, electronic document, accessed 06-06-2022.

[12] Cosley, Joseph C. Cosley, 1945. A Short Story of Kootenai Brown, published privately.

[13] Grove, Richard, Joám Evans Pim, Miguel Serrano, Diego Cidrás, Heather Viles, and Patricia Sanmartín. 2020. “Pastoral Stone Enclosures as Biological Cultural Heritage: Galician and Cornish Examples of Community Conservation” Land 9, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9010009

[14] Ekblom, Anneli; Shoemaker, Anna; Gillson, Lindsey; Lane, Paul; Lindholm, Lark-Johan, 2019, Conservation through Biocultural Heritage – Examples from Sub-Saharan Africa. Land 8, no 1: 5. Electronic document, accessed 02-06-2022 https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/8/1/5

The images within this gallery come from a variety of sources. The historical images were sourced from the Glenbow Library and Archives, National Parks Services Archives, and the Parks Canada Archive. The modern images were collected by the Capture2Preserv team, Kyle Canning of Carto Canada, and Edwin Knox.

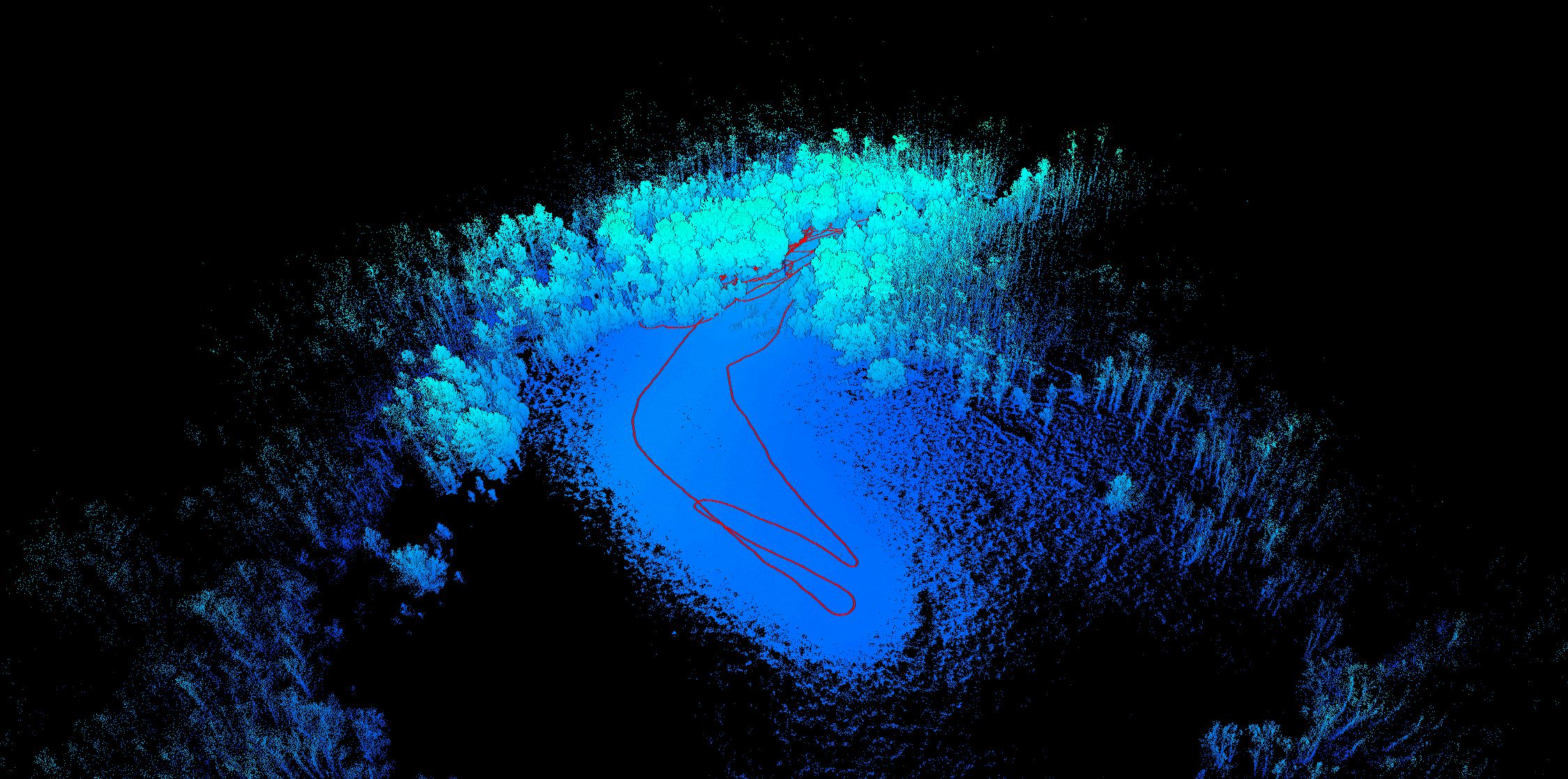

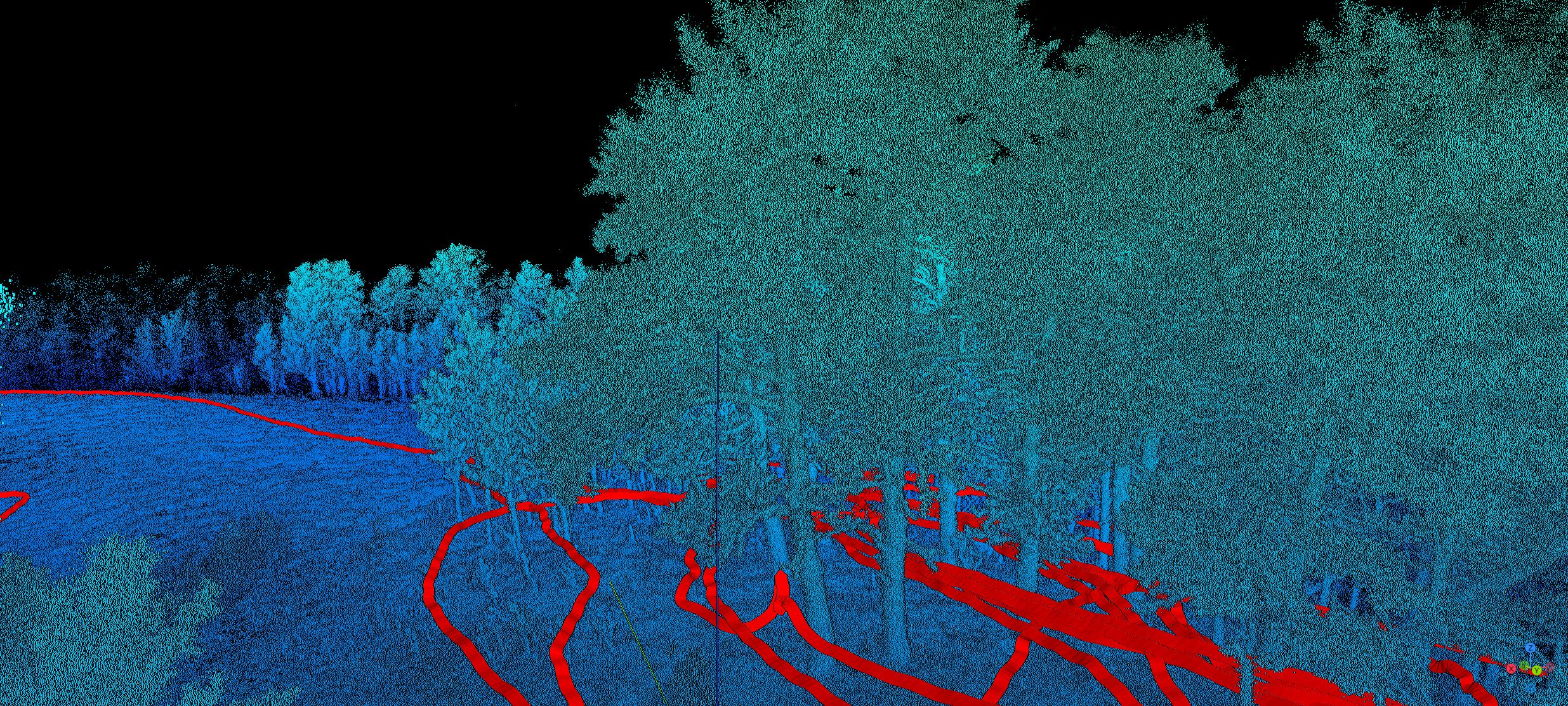

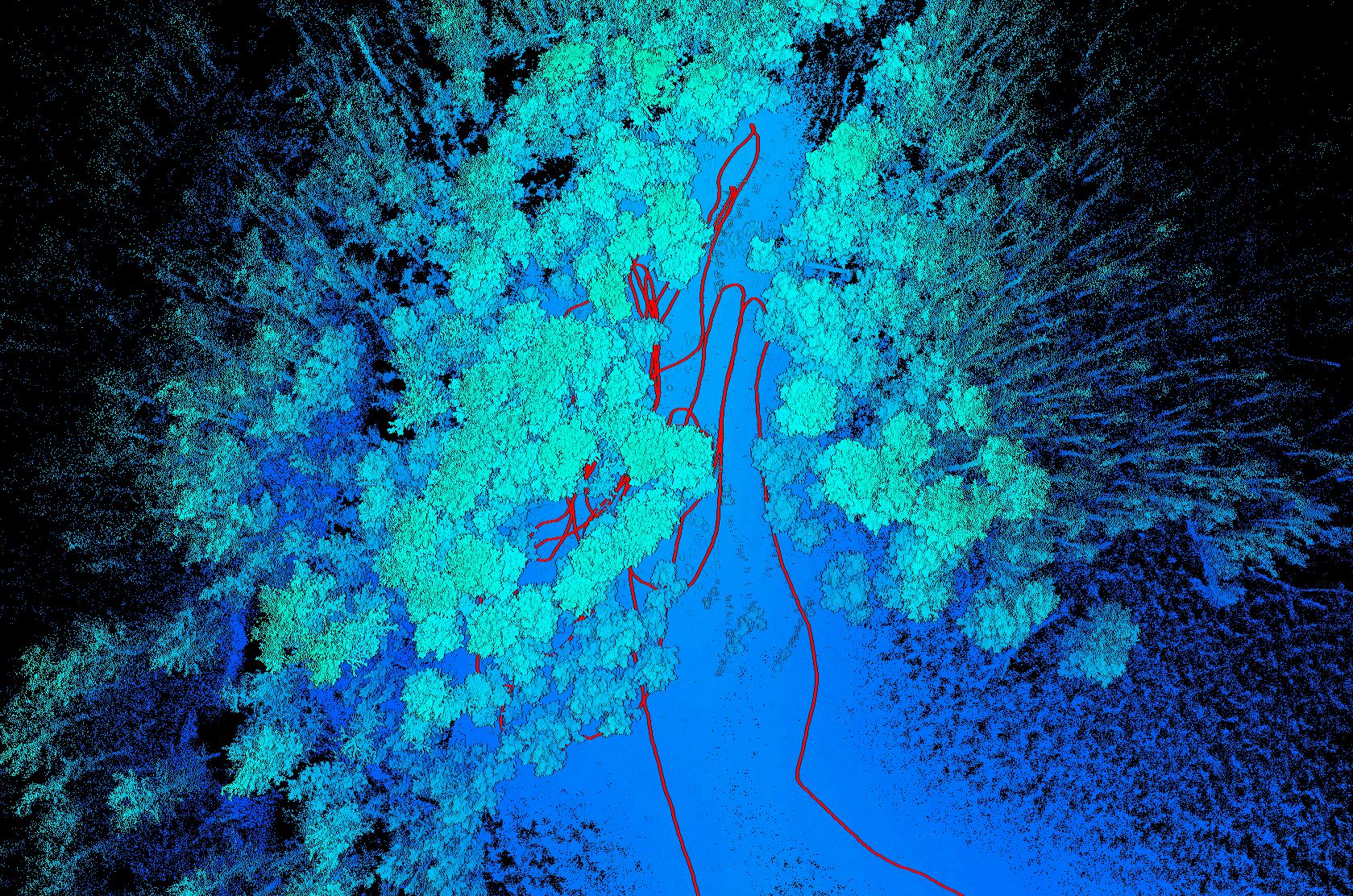

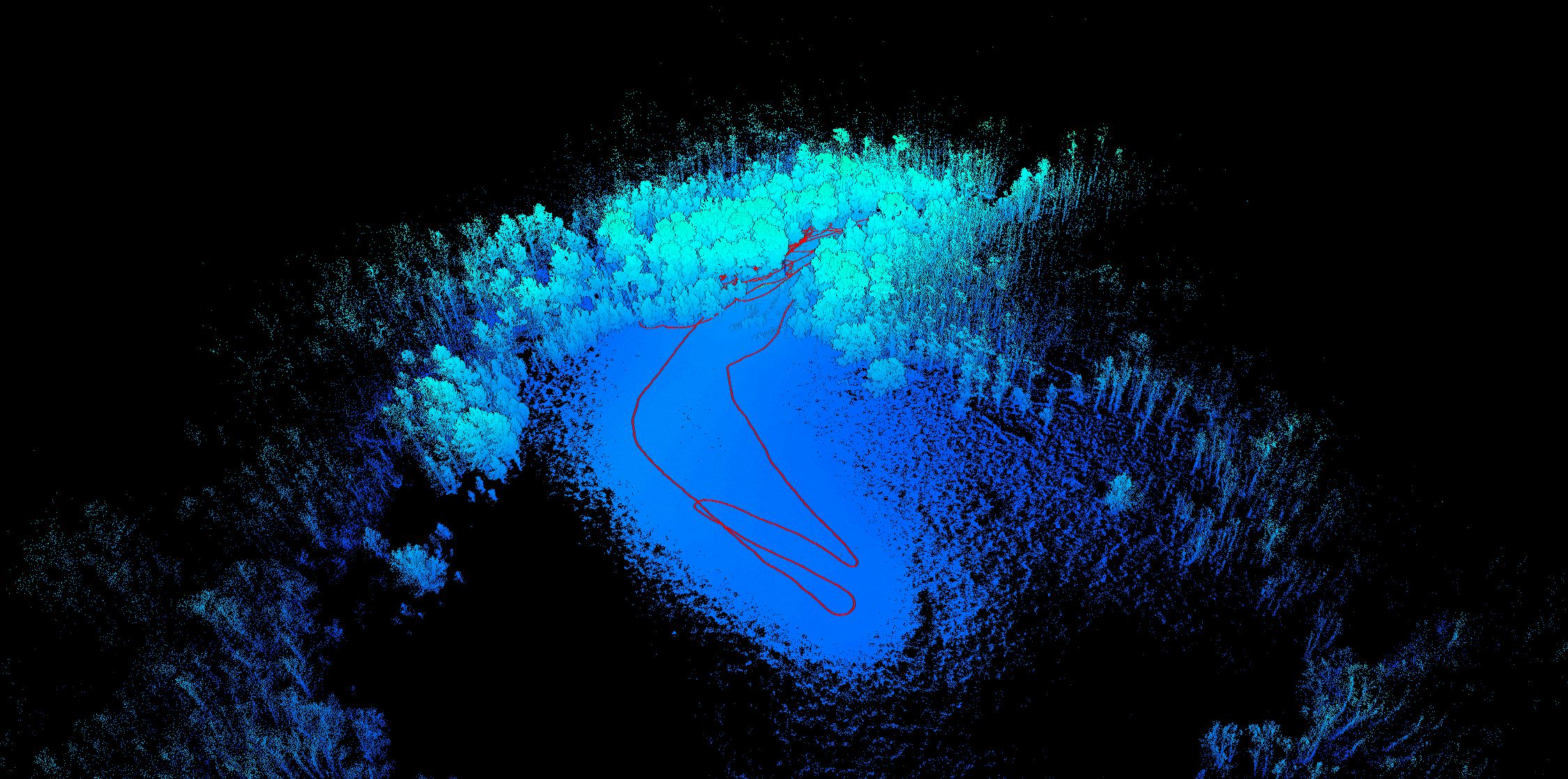

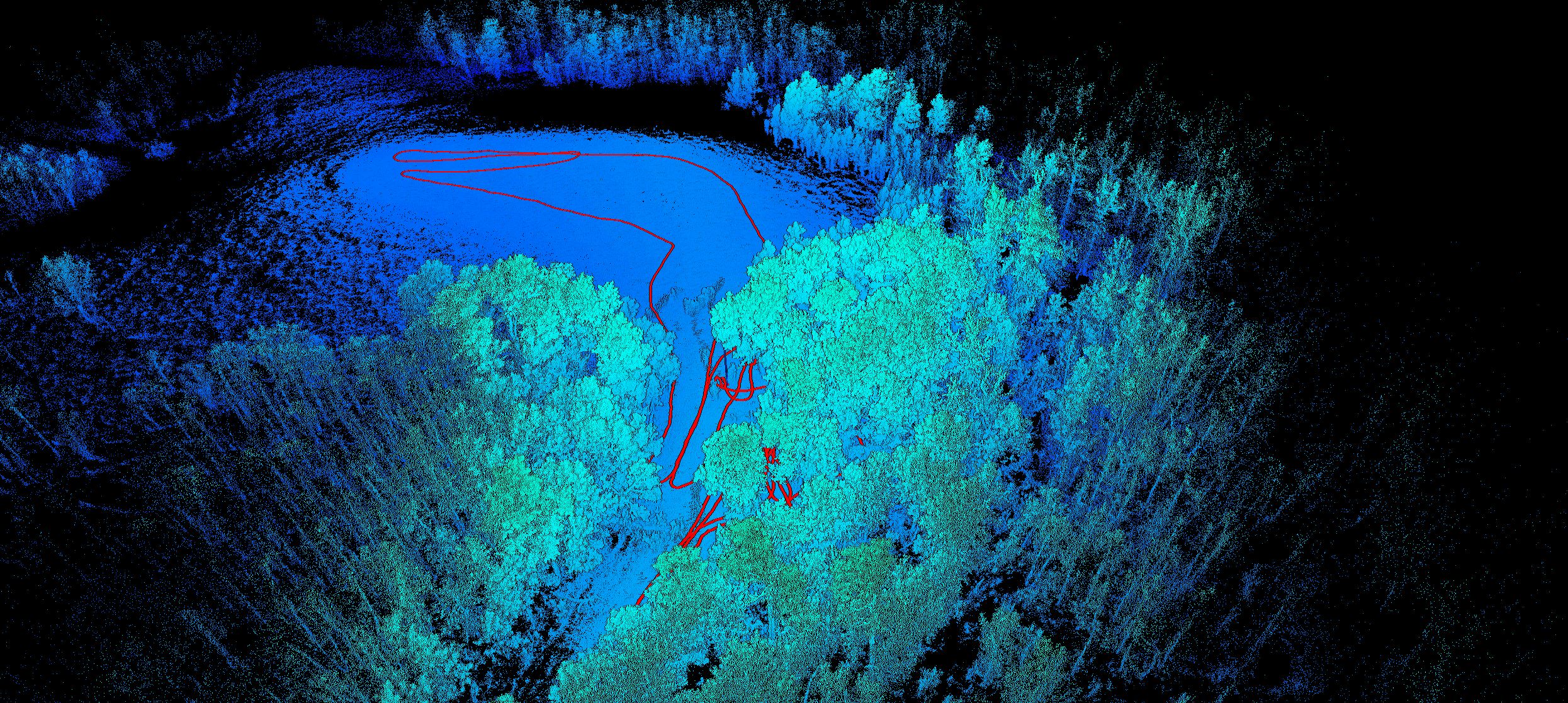

The Capture2preserv team worked with the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Parks Canada and Carto Canada to record the Kootenai Brown Poplar Grove Cabin Site. The site was recorded due to the inevitability that the culturally modified trees would eventually deteriorate and be lost. The site was recorded with the GeoSlam Zeb Horizon and the FireFly 8SE camera, this is a handheld mobile laser scanner, which uses SLAM (Simultaneous Localisation and Mapping) technology. This technology allows for large areas to be recorded in much shorter periods than traditional terrestrial laser scanning. The camera provides video data to colourise the point cloud. Two 20 minute sessions were all that were required to map the trees and the entire meadow where Kootenai Brown’s cabin once stood. The first scan concentrated on the CMTs and the location of the cabin, the second scan took a wider view and recorded the extent of the meadow in which the trees and cabin location were located.

Path of Movement Followed by the GeoSlam through the Poplar Grove

Open Access Scanning Data

The cleaned data files for this project are available for download from the archive repository. Scans are .las file format. Please download the metadata template to access metadata associated with each file. All data is published under the Attribution-Non-Commercial Creatives Common License CC BY-NC 4.0 and we would ask that you acknowledge this repository in any research that results from the use of these data sets. The data can be viewed and manipulated in CloudCompare an opensource software.