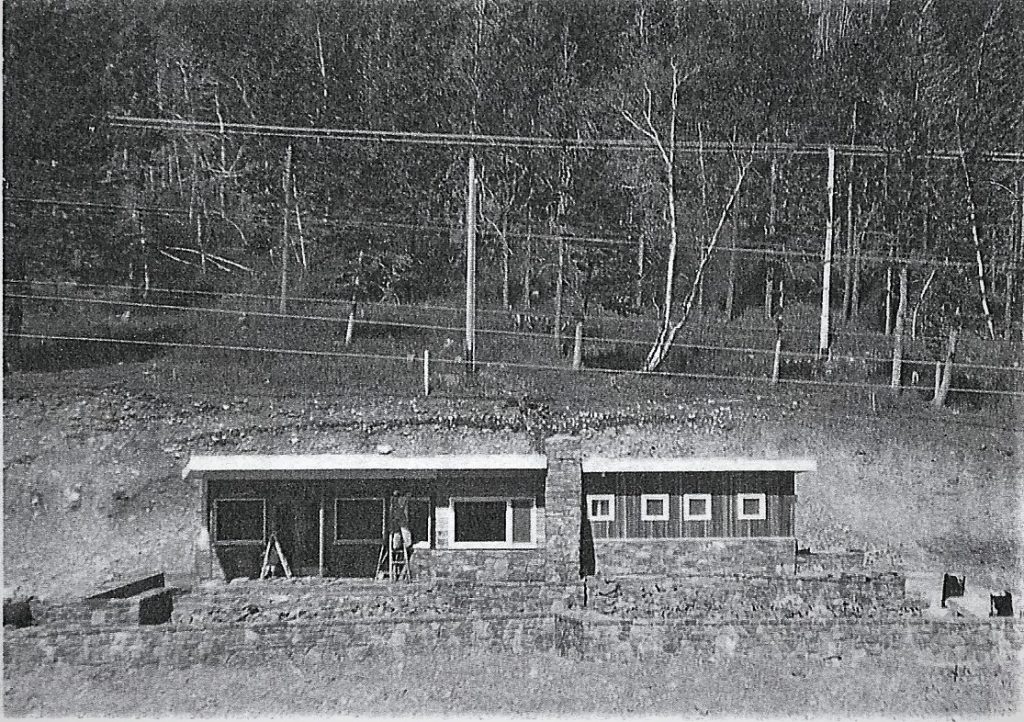

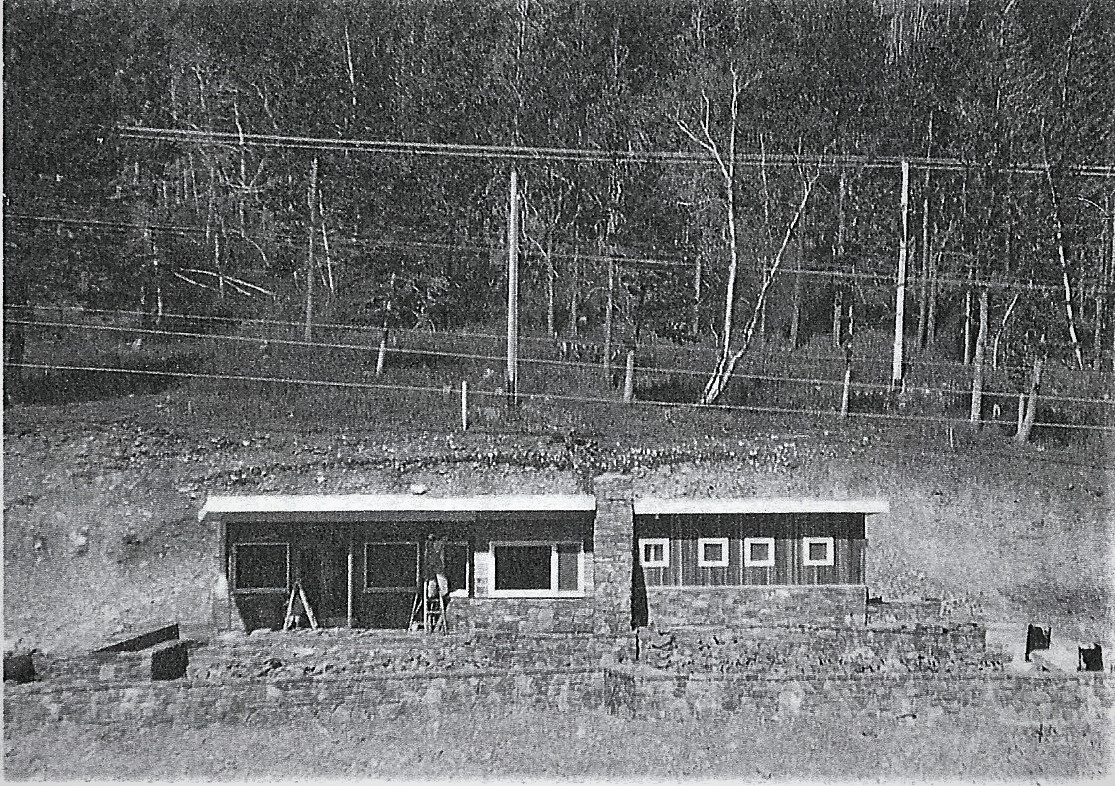

Information Bureau, Waterton Lakes National Park

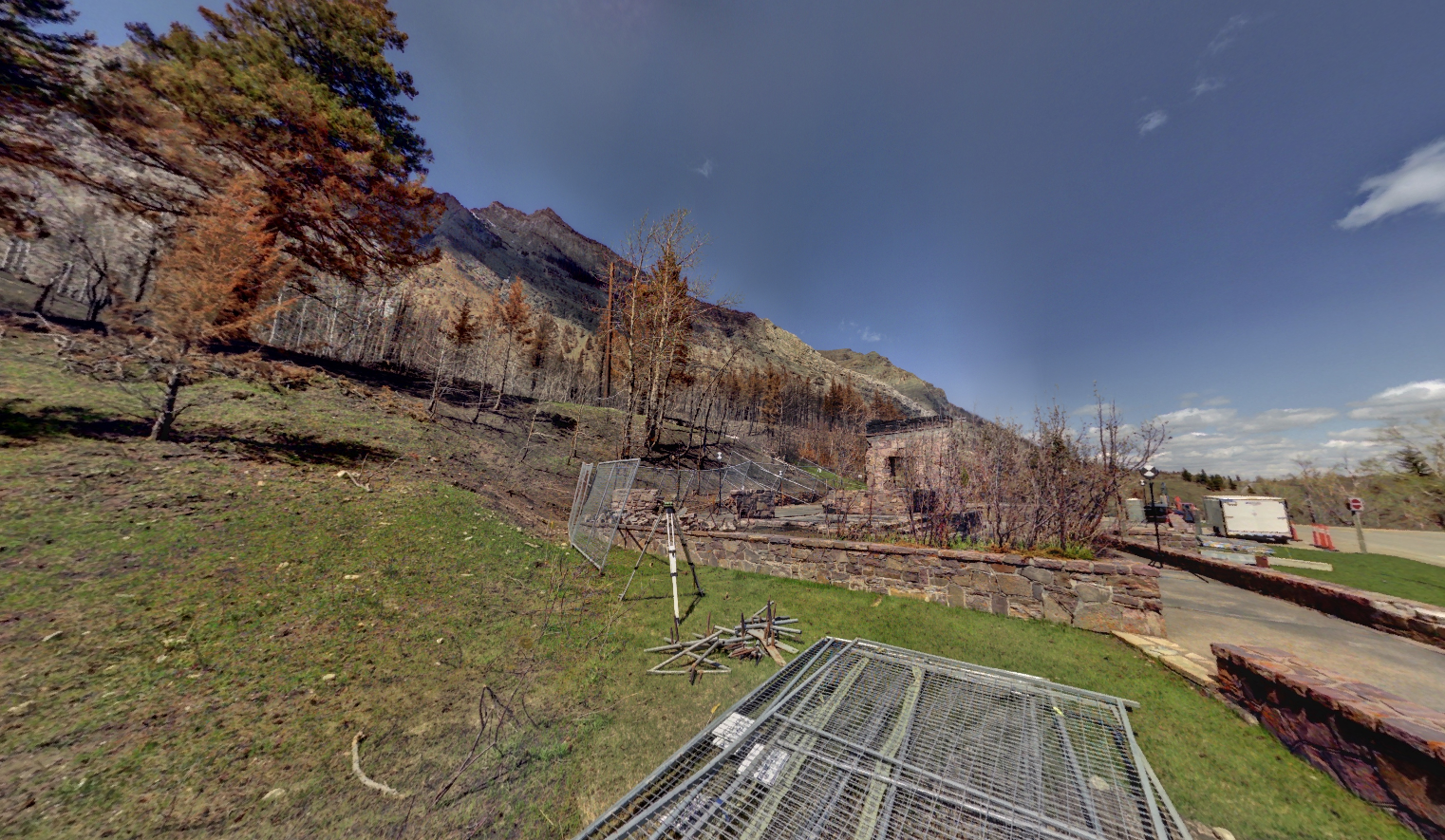

The Information Bureau was constructed in 1958 with distinctive stonework on the exterior; the stonework included a false chimney/buttress that was the main entrance to the building [1]. This small (56 m²) single storey structure was built into the hillside to provide a prominent and purpose-built location for the growing number of tourists visiting Waterton Lakes National Park [1]. This building provides an excellent example of International Style architecture that was prominent in the park throughout the 1950s and 60s [1]. This is a subsampled point cloud of what remained of the Visitors Bureau, post fire. The masonry has since been removed from the site.

Region:

Southwest Alberta

Field Documentation:

May 7, 2018

Field Documentation Type:

Terrestrial LiDAR

Culture:

Canadian

Historic Period:

1958CE

Latitude:

49.060299

Longitude:

-113.90846

Datum Type:

NAD 83

Threat Level

Waterton Lakes National Park

Waterton Lakes National Park started life as a forest reserve in 1895. The park’s boundaries and name have changed over the years [2,3]. Impacts from ranching, oil, fishing, and natural disasters played a role in those changing boundaries; however, the Lower, Middle and Upper Waterton Lakes were always at the centre of those changes [2]. The park now protects 505 km² of ecologically and culturally diverse mountain and prairie landscape [4]. This unique landscape is also recognised in the United States in Glacier National Park, and together these two parks became the first International Peace Park in 1932 [5]. Since then further designations have been bestowed on Waterton Lakes National Park: a Biosphere Reserve (1979), a UNESCO World Heritage Site (1995), and an International Dark-Sky Park (2017) [5,6].

The human history of the Waterton Lakes National Park area stretches back some 10,000 years, with the first people arriving soon after the last glacial retreat [2], and it has been continually occupied since. The Blackfoot and Kootenay peoples were both utilising this area for travel, trade, fishing and hunting [2,7]. While the influence of Europeans was felt as early as the 1790s through trade, the first European settler, John George “Kootenai” Brown did not make Waterton his home until 1877 [2]. The townsite of Waterton started life at the narrows between Middle and Upper Waterton Lakes and began as a seasonal site in 1895 [2]. The “oil boom”of 1900-1919 at Oil City, Cameron Creek, stimulated the growth of the Waterton townsite, which moved from the narrows to its present location at the Cameron Creek Alluvial Fan [2]. The townsite had another boom in the 1920s when Waterton became a very popular tourist destination with many new park buildings constructed, and this trend has continued with the further development of the Waterton townsite [2].

Information Bureau

With the tourism boom in the 1920s the first Information Bureau was opened at Waterton Lakes National Park in 1929, following the success of the one opened in Banff National Park [8]. This bureau was located in the Waterton townsite attached to the Park Administration Building [1]. In 1957 construction started on a new Information Bureau that was in a more visible location on Entrance Road outside of the townsite, across from the Prince of Wales Hotel [1,9]. The new bureau was designed in the International Style, which also influenced the design of other buildings within the park during the 1950s and 60s [1]. This style would typically have flat or low-pitched roofs, horizontal massing, hard angular edges, and a lack of applied decoration [8]. In Waterton Lakes National Park, stonework was incorporated into this style to continue the tradition of using local stone as a decorative feature on park facilities from the 1920s by the park’s architect W.D. Cromarty [1, 10]. The doors of the new Information Bureau finally opened in June 1958 [11]. This building served Parks Canada for almost 60 years before it was severely damaged in the Kenow Wildfire in September 2017 [12]. In the spring of 2018, we documented the remaining stonework to provide a record of that tradition. A new visitor centre is going to be built in the townsite in 2019 [13].

Threats to Heritage

Natural disasters, such as flooding, wildfires, and drought are not new to Waterton Lakes National Park [2], but over the last several decades, these types of events have seen an increase globally due to the effects of climate change. In Alberta alone, we have seen the devastating effects of wildfires at Slave Lake (2011), Fort McMurray (2016), and Waterton (2017), and the impacts of flooding in Calgary (2013). In addition to these naturally occurring events, there are also human impacts to consider at heritage sites, such as war, development, and looting, which have also seen an increase with a growing population. While these particular events do not have a direct impact on Waterton, the growing numbers of visitors do [14]. Visitors are an important part to the successful long-term operations at the park, but as these numbers continue to increase in the future as well as natural threats from climate change, heritage sites will need to be increasingly monitored, recorded, and protected.

Notes:

This site is located on Treaty 7 Territory of Southern Alberta, which is the traditional and ancestral territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy: Kainai, Piikani and Siksika as well as the Tsuu T’ina Nation and Stoney Nakoda First Nation. This territory is home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3 within the historical Northwest Métis Homeland. We acknowledge the many First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have lived in and cared for these lands for generations. We are grateful for the traditional Knowledge Keepers and Elders who are still with us today and those who have gone before us. We make this acknowledgement as an act of reconciliation and gratitude to those whose territory we reside on or are visiting.

[1] Mills, Edward. 1998 Waterton Lakes National Park: Built Heritage Resource Description and Analysis, Outlying Facilities (Non-Townsite). On File: Parks Canada, Calgary.

[2] MacDonald, Graham, A. 2000 Where the Mountains Meet the Prairies: A History of Waterton Country. University of Calgary Press, Calgary.

[3] Waterton Lakes National Park: Park History. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/waterton/culture/histoire-history Accessed: October 16, 2018.

[4] Waterton Lakes National Park: 2010 Managment Plan Highlights. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/waterton/info/index/directeur-management/pointssaillants-highlights Accessed: October 16, 2018.

[5] Waterton Lakes National Park: Designation Information. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/waterton/culture/designation Accessed: October 16, 2018.

[6] International Dark-Sky Association: Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park (Canada/U.S.). http://darksky.org/our-work/idsp/parks/waterton-glacier/ Accessed October 16, 2018.

[7] Rueter, Annie. 2018 Archaeologists Uncover New History in Waterton Lakes National Park After 2017 Wildfire. Canadian Geographic, 10 August. https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/archeologists-uncover-new-history-waterton-lakes-national-park-after-2017-wildfire Accessed October 18, 2018.

[8] Lethbridge Herald. 1928 Alberta Body Will Operate Bureau at Waterton National Park Next Season, 20 September: 1. https://digitallibrary.uleth.ca/digital/collection/herald/id/10395/rec/20 Accessed October 18, 2018.

[9] Lethbridge Herald. 1957 Start Work on New Bureau Building in Waterton Park, 13 Septemeber: 10. https://digitallibrary.uleth.ca/digital/collection/herald/id/8677/rec/1 Accessed October 18, 2018.

[10] Parks Canada. 2018 Former Information Bureau (1958), Post Fire Situation, Water Lakes NP. On File : Parks Canada, Calgary.

[11] Lethbridge Herald. 1959 Wonderful Waterton, 17 January: 8. https://lethbridgeherald.newspaperarchive.com/lethbridge-herald/1959-01-17/page-6/ Accessed October 18, 2018.

[12] Rieger, Sarah. 2018 Design Chosen for Contentious Waterton Visitor Centre. CBC, 12 January. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/waterton-visitor-centre-design-1.4486129 Accessed October 18, 2018.

[13] Parks Canada. 2018 Waterton Lakes National Park: New Visitor Centre, 29 March. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/waterton/info/public Accessed October 19, 2018.

[14] Statista. 2018 Number of Visitors to Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada from 2011 to 2018 (in thousands), June. https://www.statista.com/statistics/501627/visitors-to-waterton-lakes-national-park/ Accessed October 19, 2018.

Historical and modern images were sourced from Parks Canada from 1958 to 2017 after the Kenow wildfire. Images of the scanning process were provided by the Capture2Preserv Team.

Digitally Capturing the Information Bureau, Waterton Lakes National Park

The Digitally Preserving Alberta’s Diverse Cultural Heritage project was approached by Parks Canada to record the burnt remains of the 1950s Information Bureau prior to their destruction. The stonework remains were recorded with the Z+F 5010X scanner and six paddle targets. The paddle targets were strategically placed around the building and external area, such that no less than three were visible in each scanning location. There were 21 scanning locations that encompassed the building and external areas in an S shape. The scans were registered using Z+F Laser Control software and then exported into AutoDesk ReCap for further processing. The resulting point cloud was imported into AutoDesk ReMake to create a 3D model of the building.

Scan Locations

Open Access Scanning Data

The raw data files for this project are available for download from the archive repository. Scans are .las file format. Please download the metadata template to access metadata associated with each file. All data is published under the Attribution-Non-Commercial Creatives Common License CC BY-NC 4.0 and we would ask that you acknowledge this repository in any research that results from the use of these data sets. The data can be viewed and manipulated in CloudCompare an opensource software.