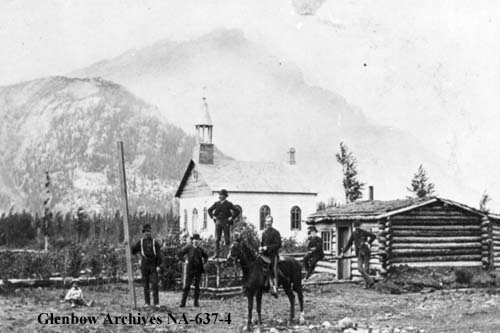

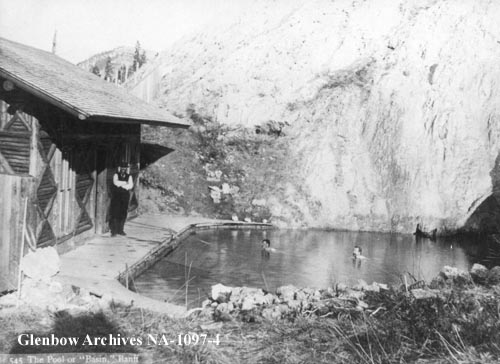

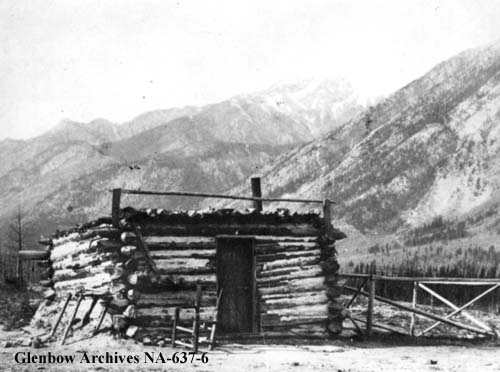

Miner’s Cabin

This wooden cabin is a single room building with a 23.32 m² footprint and was built around 1885. The cabin was original built in Banff, Alberta, but was given to Heritage Park by the Glenbow Foundation in 1964 and added to the park to illustrate the rustic living conditions of the miners who came to the Rocky Mountains searching for gold or other minerals [1].

Region:

Southwest Alberta

Field Documentation:

April 14, 2016

Field Documentation Type:

Terrestrial LiDAR

Culture:

Euro-Canadian

Historic Period:

1885CE

Latitude:

50.982516

Longitude:

-114.107186

Datum Type:

NAD 83

Threat Level

The Cabin

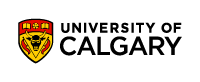

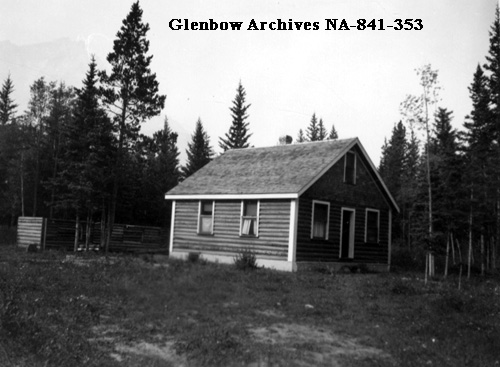

The cabin was constructed with horizontal log-rounds that were dovetailed at the corners with a shingled gable roof and was likely made from locally available materials such as pine or spruce [2]. This cabin type is typical of central Alberta for the pioneering settlers that came to western Canada [2]. Canada has a long history of log constructed buildings from First Nations, Inuit and Metis groups to European settlers who bought their own construction techniques with them [2]. This cabin was most likely built by two brothers, George and William Fear, who arrived from London in 1885 [3]. The cabin was behind the Wilson & Fear General Store in Banff, Alberta. The Fear brothers were fur traders that partnered in 1893 with Tom Wilson, a renowned outfitter and guide [3]. The cabin was used to accommodate the taxidermy needs of tourists coming to Banff and area to hunt wild game. Bobby Robertson worked as the taxidermist from 1885 til 1906 or 1907 [1].

Banff National Park

The Miner’s cabin that is now located at the Heritage Park has close ties to the early tourism and development of sports hunting in the Banff National Park area [4]. Banff townsite started life as a rail siding, known as Siding 29, and by 1883 had been renamed Banff, most likley after Banff, Scotland either by Lord Starthcona or John MacTavish, the Scottish born Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) land commissioner [5, 6]. The beginnings of the national park start with a dispute between several claimants for the (re)discovered Cave and Basin Hot Springs, which ended in 1885 when the Banff Hot Springs Reserve was created, a 10 mile square area around the springs, in which the Federal Government was responsible for the buildings and business operations [7]. In 1887 the Rocky Mountains Park Act extended the reserve to approximately 260 square miles which encompassed the townsite of Banff and surrounding area [7]. Then in 1930, the National Park Act was passed, and the park name was officially changed from Rocky Mountains Park to Banff National Park and was further extened to approximately 2,564 square miles in size [7]. However, prior to European arrivals the First Nations people had a variety of names for this area. The Blackfoot called it Nato-oh-sis-koom, meaning “holy spring”; Nakoda called it Minihapa while the Cree called the area Nipika-Pakitik, both names refer to the Cascade Mountain falls; and the Tsuu T’ina use the name Tsa-nidza which means “in the mountains” [6].

When the hot springs were designated as a reserve it was these springs that were seen as a tourist attraction, like the European spas of the day, by William Pearce (land surveyor) and Thomas White (Minister of the Interior) [5]. Bath houses and hotels were soon erected near by and by the beginning of the twentieth century tourist attractions included a zoo, animal paddocks, a museum of natural history, and a boat-house and the park also became popular for hunting, climbing, and fishing [5]. By 1932, the town of Banff had nine commercial hotels, eight restaurants, and eight souvenir stores [8]. As with any frontier settlement natural resources were exploited in the area with lumber and coal extraction which supported the new park, Banff, and CPR. Of particular interest is the fact that Bankhead mine was actually placed inside the newly created park, only a few kilometers east of Banff, and was in production from 1903-1922, but was unlike most mining towns [9]. This town was designed with tourism in mind and was a model town developed by CPR with modern amenities [9]. When the mine was decommissioned in 1922 many of the buildings were moved to Banff, Canmore and some further afield to Calgary [9].

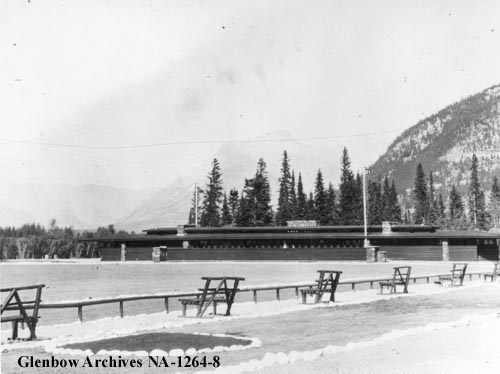

Architecture of Banff

Much of the architecture in Banff was designed with tourism in mind with luxury hotels and other attractions such as museums. One building of great significance in Banff is the Pavilion that was commissioned, in 1911, by the Canadian Department of the Interior and designed by the notable US architect Frank Lloyd Wright and his only Canadian student Francis C. Sullivan[10]. This is the only public building to have been designed and built in Canada by Wright. The pavilion was designed in Wright’s Prairie Style and was 1300 square meters in size [10,11]. It had three large fireplaces, westward windows with a panoramic view of the mountains, a ladies’ and gentlemen’s retiring area, galley kitchens and lavatories [10]. Building materials included leaded glass windows, fieldstone, and indigenous timer [10]. The Pavilion was completed in 1914 but only stood for 25 years [12]. Over it’s relatively short lifespan, it housed a WW I quartermaster stores and then in the 1920’s was a place where weekend “old money” would converge [10]. The Banff Pavilion was not without controversy. The residents of Banff wanted a practical recreation area that would include a curling rink, hockey area, etc. but these wishes were “ignored by the ‘overlords’ at Ottawa” as stated in a 1913 Craig and Canyon newspaper article [10]. None the less, the Pavilion was built. In 1933, a flood completely inundated the Pavilion and in 1939 it was demolished [10].

The more humble architecture, such as the Miner’s cabin at Heritage Park, were built during the early years of Banff or what was known as Siding 29. An example of this structure type in the Banff area is the McCabe and McCardell shack, some of the claimants to the Cave and Basin Hot Springs. Also at Bankhead mine there were 12 similar miner cabins built, known as the 12 disciples [9]. While most of the town was provided with electricity and indoor sewage systems these 12 cabins had non of these modern services and as a consequence were only $5 a month compared to the $7.50 to $10 for those houses with modern services. These log cabins used local materials, fairly simple construction techniques, and were relatively quick to construct.

Notes

[1] Heritage Park. 2018. Personal communication, e-mail (on file).

[2] Wonders, William, C. 1979 Log Dwellings in Canadian Folk Architecture. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 69(2): 187-207.

[3] Southern Alberta Pioneers and their Descendants. 2018 Southern Alberta Pioneers and their Descendants. http://www.pioneersalberta.org/profiles/f.html Accessed: July 9, 2018.

[4] Colpitts, George 2010 Game in the Garden: A Human History of Wildlife in Western Canada to 1940. UBC Press, Vancouver and Toronto.

[5] Luxton, Eleanor, G. 2008 Banff Canada’s First A National Park: A History and a Memory of Rocky Mountains Park. Summerthought Publishing, Banff.

[6] Aubrey, Merrily K. (ed.). 2006 Concise Place Names of Alberta. University of Calgary Press, Calgary.

[7] Robinson, Sheila 1980 A Report on the Natural and Human History of Banff National Park (The Book of Banff). Parks Canada, Ottawa.

[8] Jones, Stephen B. 1933 Mining and Tourist Towns in the Canadian Rockies. Economic Geography 9(4): 368-377.

[9] Gadd, Ben 1989 Bankhead the Twenty Year Town. The Coal Association of Canada, Calgary.

[10] Sinclair, Brian R. and Terence J. Walker. 1997 Frank Lloyd Wright’s Banff Pavilion: Critical Inquiry and Virtual Reconstruction. APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology 28 (2/3): 13-21.

[11] Steiner, Douglas M. 2010 Wright Studies, Banff National Park Pavilion, Banff, AB (1911) (S. 170). http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/PhRtS170.htm Accessed: March 6, 2018.

[12] Frank Lloyd Wright Revival Initiative. 2018 Frank Lloyd Wright Revival Initiative. http://flwrevivalinitiative.org/banff-park-pavilion/ Accessed: March 13, 2018.

All historical images were sourced from the Glenbow Archives and modern images provided by the Capture2Preserv Team.

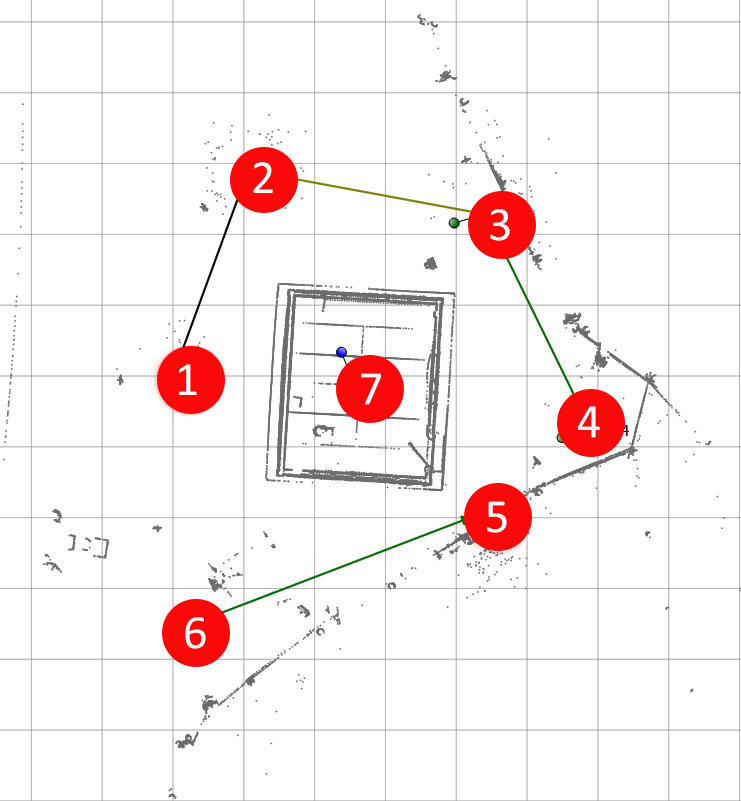

Digitally Capturing the Miner’s Cabin

In the early days of the Digitally Preserving Alberta’s Diverse Cultural Heritage project we needed test subjects to hone our skills. With this in mind we approached the Heritage Park about scanning one of their simpler structures and the Miner’s Cabin was recommended. We were fortunate enough to be able to record the structure prior to the park opening for the season. The Z+F 5010X scanner and six paddle targets were used to record the cabin. The six paddle targets were strategically placed around the exterior of the cabin, such that no less than three were visible from each scanning location. The building was then captured in its entirety from six external scanning locations and a single internal scanning location. The scans were registered using Z+F Laser Control software, and then exported into AutoDesk ReCap for further processing. The resulting point cloud was imported into AutoDesk ReMake to create a 3D model of the building.

Scan Locations

Open Access Scanning Data

The raw data files for this project are available for download from the archive repository. Scans are .las file format. Please download the metadata template to access metadata associated with each file. All data is published under the Attribution-Non-Commercial Creatives Common License CC BY-NC 4.0 and we would ask that you acknowledge this repository in any research that results from the use of these data sets. The data can be viewed and manipulated in CloudCompare an opensource software.