The Springbank Hill Wind-Pump

Upon European arrival to North America, windmill technology was quickly adapted to pump well water in order to allow for the settlement of the arid prairie environments. The use of wind-pump technology became a main feature of ranches and farms in the West, with popularity expanding through to the 1930s. The Springbank Hill wind-pump is a prime example of the use of these wind-pumps in the settlement of Alberta. This is a subsampled point cloud of the windmill which has subsequently been demolished.

Region:

Southwest Alberta

Field Documentation:

December 4, 2017

Field Documentation Type:

Terrestrial LiDAR

Culture:

Canadian

Historic Period:

CE

Latitude:

51.037119

Longitude:

-114.202296

Datum Type:

WGS84

Threat Level

Wind-Pump Technology in North America

Well known today for their use in generating electric power, windmills originally came to the West for a variety of other important uses. Europeans brought windmill technology to North America in the seventeenth century and continued to use them for long-established practices such as sawing wood, grinding grain, and churning butter [1]. Versatile in their use and relatively inexpensive and easy to construct, windmills rapidly became a common feature throughout the North American landscape [1, 2].

The ability to harness wind power was particularly important for the settlement of arid environments, such as the American Great Plains and the Canadian Prairies where windmills were used to pump water. While the prairies did have plenty of water, it was contained in scattered lakes and rivers or deep below the surface in underground aquifers. To obtain underground water, settlers relied on wells, which would be anywhere from 2.5 to 9 m once constructed [1]. To haul water out of these wells to support agricultural fields and ranches was an enormous effort, taking valuable time and energy from other pursuits. What ranchers needed was something inexpensive that could pump water all hours of the day without taking away from the rest of the operations on a farm, ranch or homestead [1].

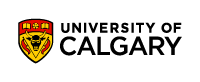

The solution was found in the windmill technology Europeans had already brought over with them. Simple to construct and overall inexpensive and long-lasting, the windmill was ideal for the prairie environment. The wind’s power would rotate the spinning blades, which would then turn sets of gears within the windmill, converting the wind to mechanical energy [1, 2, 3]. This mechanical energy powered the primary element in the wind-pump, which was the underground pumping cylinder. The cylinder was outfitted with a type of plunger, and as the plunger moved up and down it captured water and pulled it upwards [2]. The pump was built deep into aquifers and could provide a fairly constant source of water for settlers in these open and arid environments [1].

While examples of wind-pumps have been found as early as the 9th century in what is now Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan, the importance of wind-pump technology to settlement in Canada and the United States has left them as referred to as an American innovation [1, 3]. Not only were they highly important for ranching and agricultural endeavours, in some areas such as California wind-pumps were the basis of self-contained domestic water systems and helped fill town’s water-towers and reservoirs [3].

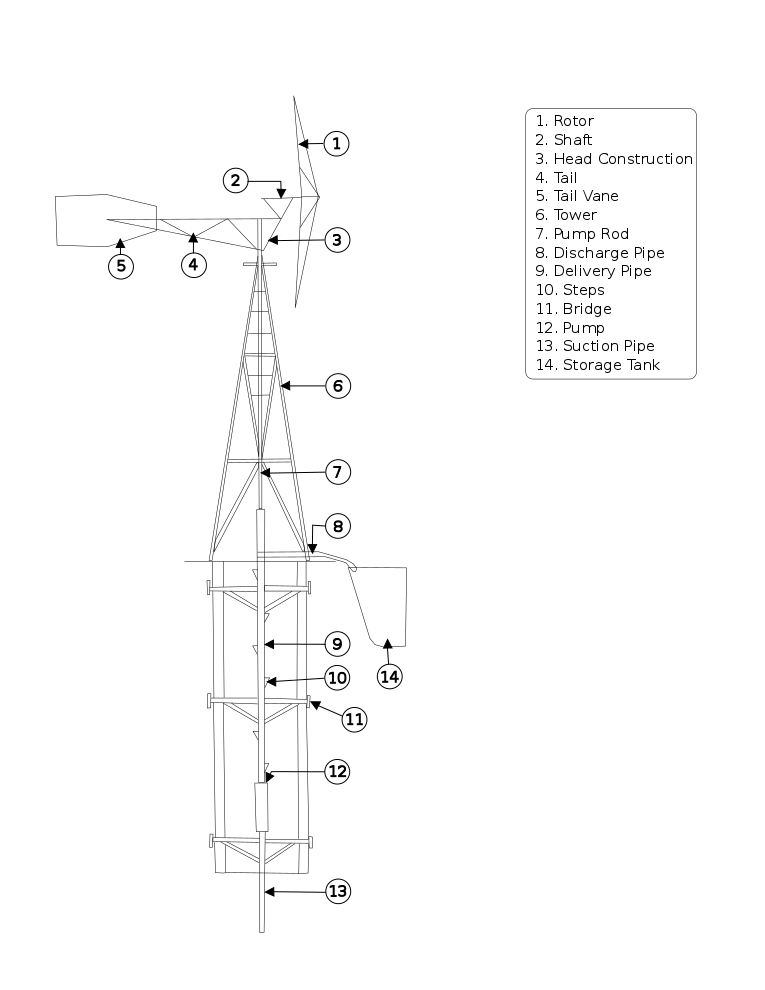

In 1854 Daniel Holladay revolutionized the technology by creating a self-regulating wind-pump in which a centrifugal governor could control the speed of the blades and rotate the head of the windmill [3, 4]. Self-regulating windmills were especially important as they decreased damages from high-speed winds, and allowed for maintenance to be conducted as infrequently as once a year [3, 4]. Another important innovation to the design of windmills occurred in 1872 when steel blades and towers started to replace wooden construction, increasing popularity of the technology even more in open areas with wood shortages [3,4]. At their peak in the 1930s, it was estimated that over six million wind-pumps were in use in the United States [3,4]. As electricity started to become an economic alternative in the later part of the 1930s, electric pumps were favoured over wind-powered alternatives and the wind-pump started to disappear [4].

The Springbank Hill Wind-Pump

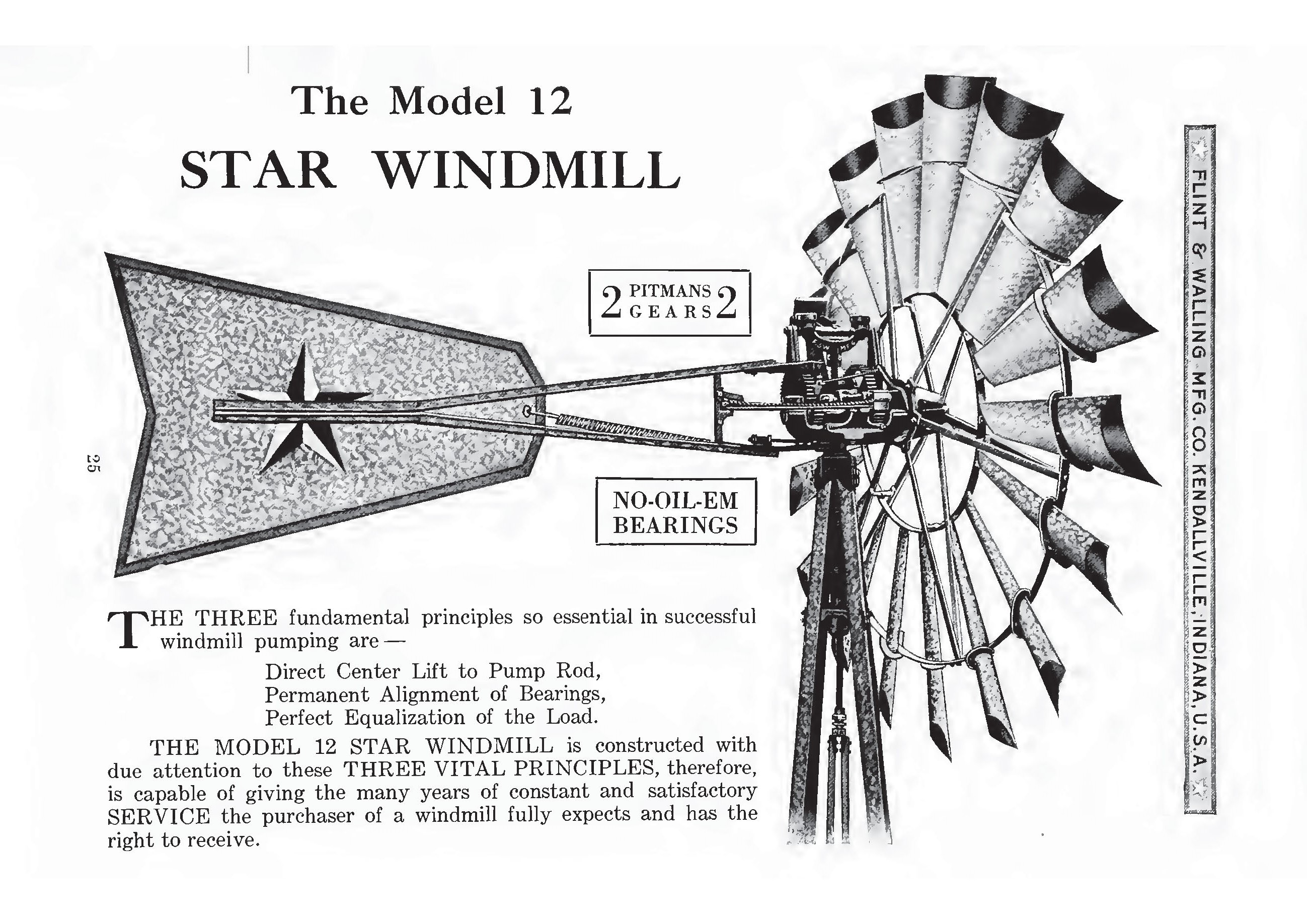

In Canada, the number of windmills in operation is less well known. According to the Alberta Land Settlement Infrastructure project, between 1885 and 1911 there were at least 52 windmills in operation within the province [5]. As wind-pumps continued to grow in popularity through to the 1930s, it is likely that this number was much higher. However, the wind-pumps were certainly more popular in the United States and most Canadian pumps were imported from American manufacturers [5]. The Springbank Hill wind-pump was imported from the Flint & Walling MFG. Co. Kendallville Ind. U.S.A., which was established in 1866 and continues to trade today [6]. McAuley, Bell & Morris were the wholesale plumbing and building supply firm, located at 338 8th Ave West, Calgary, who supplied this wind-pump to an acreage southwest of Calgary [7]. This firm was built from the Canadian Western Manufacturing Company where Charles E. Morris worked upon coming to Calgary in 1917. In 1924 when Morris partnered with T.A. McAuley and J. Leslie Bell, McAuley, Bell & Morris was officially established [7]. Under this ownership the firm operated for 20 years, and then was sold as the original owners decided to retire, but continued to run under the same name [7].

The Springbank Hill wind-pump consisted of a Flint & Walling Star model windmill, with a steel tower, tail vane (no longer attached), rotor and shaft, standing at around 14 meters tall. The pump and base of the windmill tower were housed in a small wooden single storey building with a second structure attached to the west of the wind-pump.

Notes:

This site is located on Treaty 7 Territory of Southern Alberta, which is the traditional and ancestral territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy: Kainai, Piikani and Siksika as well as the Tsuu T’ina Nation and Stoney Nakoda First Nation. This territory is home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3 within the historical Northwest Métis Homeland. We acknowledge the many First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have lived in and cared for these lands for generations. We are grateful for the traditional Knowledge Keepers and Elders who are still with us today and those who have gone before us. We make this acknowledgement as an act of reconciliation and gratitude to those whose territory we reside on or are visiting.

[1] Alberta Culture and Tourism, 2018 Electricity and Alternative Energy. Electronic document, http://www.history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/energy/wind-power/wind-power-in-north-america-and-the-development-of-windpumps/default.aspx, accessed on November 15, 2018.

[2] Schrunn, Ryan, 2018 The Iconic Windmills that Made the American West. Electronic document, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/windmills-water-pumping-museum-indiana, accessed on November 15, 2018.

[3] Khasan, Haydar, 2016 Design and Development of Wind Power Water Lifting Pump Mechanism. IJSTE International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering 2(12):651-655.

[4] Alberta Culture and Tourism, 2018 The Halladay and Jacobs Windmills. Electronic document, http://www.history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/energy/wind-power/wind-power-in-north-america-and-the-development-of-windpumps/the-halladay-and-jacobs-windmills.aspx, accessed on November 15, 2018.

[5] Sandwell, Ruth, 2016 Powering Up Canada: The History of Power, Fuel, and Energy from 1600. McGill University Press, Montreal, Canada.

[6] Flint and Walling, 2018 The F&W story. Electronic document, https://www.flintandwalling.com/en-na/press/about-us, accessed on November 23, 2018.

[7] The Calgary Herald, 1946 C.E. Morris, Early Calgarian, Dies. Obituary for C.E. Morris, 9 April. Calgary, Alberta.

[8] Rastogi, T, 1982 Windpump Handbook (Pilot Edition). Tata Energy Research Institute Documentation Centre. Electronic Document, https://we.riseup.net/assests/4860/windpiump+handbook.pdf, accessed on November 28, 2018.

Images of the Springbank Windmill were provided by the Capture2Preserv Team and Stantec Consulting Ltd. The advertisement was found in the United Farmers Historical Archive.

Digitally Capturing the McAuley, Bell & Morris Wind-Pump

The windmill was scanned in 4th December 2017. It was captured using a Z+F 5010X terrestrial laser scanner. The windmill was captured from eight scanning locations, using six paddle targets. The six paddle targets were strategically placed around the exterior of the cabin, such that no less than three were visible from each scanning location. The building was then captured in its entirety from eight external scanning locations. The scans were registered using Z+F Laser Control software, and then exported into AutoDesk ReCap for further processing. The resulting point cloud was imported into AutoDesk ReMake to create a 3D model of the building.

Scan Locations

Open Access Scanning Data

The raw data files for this project are available for download from the archive repository. Scans are .las file format. Please download the metadata template to access metadata associated with each file. All data is published under the Attribution-Non-Commercial Creatives Common License CC BY-NC 4.0 and we would ask that you acknowledge this repository in any research that results from the use of these data sets. The data can be viewed and manipulated in CloudCompare an opensource software.